Understanding Veterans – Part Three

If you missed it, here’s the link to the first of this three-part series about service members and veterans: https://blog.morainepark.edu/understanding-veterans-a-three-part-series/.

Part Two was an introduction to the military’s structure, where I distinguished differences between the five service branches and addressed the influence of the entertainment industry on civilians’ understanding of military service and veterans. The second part in this series can be found at https://blog.morainepark.edu/what-is-a-nco-and-what-is-the-coast-guards-mission-understanding-veterans-part-two/ . Part Three of my blog series focuses on military discharges and a service member’s transition.

In general, when an individual initially enters the military they incur up to an eight-year service obligation. This is true whether someone joins the active components, National Guard or the Reserves; however, distinctions regarding those service commitments are apparent. The biggest difference is those on active duty perform their military occupational specialty (MOS) on a daily basis, and can decide to leave active service after three to four years, whereas those who enter the National Guard or Reserves meet on a part-time basis—traditionally one weekend a month and two weeks during the summer. If an active duty service member decides to leave prior to completing their initial eight-year obligation they often choose to enter the National Guard or the Reserves to complete their commitment, while others elect to be assigned to the Individual Ready Reserve or IRR. The IRR is a source of trained personnel who can be recalled and asked to serve, if needed. The military maintains a group within IRR to ensure additional forces can be called upon during significant conflicts or when a substantial deployment is required. Although these service members retain the rank they achieved while serving on active duty, members assigned to the IRR only receive pay if they are called to active service.

Whether a service member chooses to leave the military on their own or is forced out due to a multitude of reasons, they fall under one of six military discharge categories: (a) honorable, (b) general, (c) other than honorable, (d) bad conduct, (e) dishonorable and (f) entry-level separations. Although many factors can determine the type of discharge a service member receives, a brief explanation of each is provided below.

“Contrary to popular belief, the vast majority of those leaving the service after completing an initial enlistment are separated rather than discharged. The key difference lies in that a discharge completely alleviates the veteran of any unfulfilled military service obligation, whereas a separation (which may be voluntary or involuntary) may leave an additional unfulfilled military service obligation (MSO).”

- An honorable discharge indicates a service member has completed their duty with admirable personal and professional conduct and therefore are eligible to receive the full range of veteran benefits. Most service members who complete their service obligation go on to receive an honorable discharge.

- General discharges usually indicate a service member completed their service obligation with less than honorable circumstances. The official documents typically state the factors which led to a general discharge, and deem many veteran’s ineligible for certain benefits. A general discharge could also include conditions such as illness and injury, which might not fall under the category of a medical separation.

- Other than honorable is the most severe of the administrative discharges and is often the result of punishment in either the military or civilian court system. Because of the severity of the discharge, most service members are banned from ever re-enlisting into the Armed Forces. and are ineligible to receive most benefits provided through the Department of Veterans Affairs.

- A bad conduct discharge is a punishment for a military crime. It results in confinement to a military prison for a short period of time. Again, most veterans with a bad conduct discharge are considered ineligible for any military-affiliated benefits.

- A dishonorable discharge on the other hand is a punitive action against a military member. Serious offenses such as murder or desertion of one’s duty will often lead to a dishonorable discharge. Similar to a convicted felon, veterans with a dishonorable discharge do not receive many benefits, are often ostracized from the military community, and experience a hard time finding employment.

- Lastly, there is the entry level separation and occurs if an individual leaves the military before completing at least 180 days of service. This type of military discharge can happen for a variety of reasons, including medical issues or some sort of administrative actions, and is considered neither good nor bad; however, in many cases, individuals with this type of discharge are not classified as a “veteran”, and thus are ineligible for state and federal benefits.

Transitioning from military to civilian life can be met with mixed feelings. Many service members form strong bonds with those they have served with, and leaving can be an emotional experience.

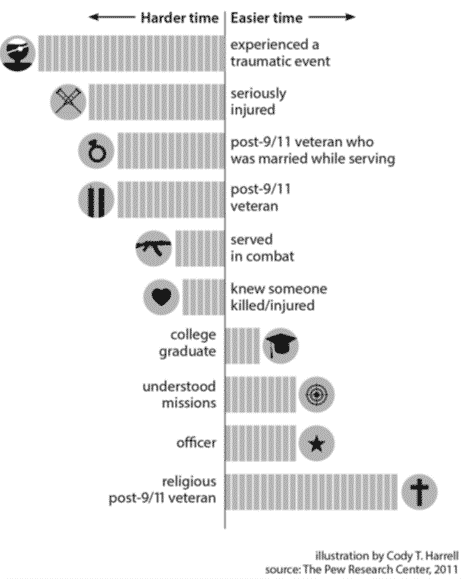

While most veterans, according to Morin (2011), report having an easy time readjusting, a small percentage have trouble with the change (see figure 1). Those who experience difficulties are often a result of deployments, specifically combat operations which can be made worse if the service member was married, sustained an injury, or perhaps knew someone who was injured or killed. Regardless, once a service member decides to exit the military, they typically pursue one of two paths—non-military employment or higher education. Some veterans eager to use the skills acquired in the military seek out military-friendly companies. Many military-or veteran-friendly companies seek veterans for hire because of their leadership experience, dependability and discipline, but often struggle to incorporate their military training in a resume that employers will understand—a challenge also experienced by veterans. For veterans interested in pursuing higher education, military education benefits, most notably the GI Bill ® which provides up to 36 months of benefits to help fund tuition, books and housing to attend school, are an appealing option. Similar to employers, higher education plays a role in veteran transitions. Often colleges will award college credits for the training and experience a service member attained while serving which can reduce the amount of benefits and time needed to complete their degrees, and also allows them to enter the workforce sooner. Regardless of which path a service member takes, once the decision is made to leave, there are many benefits available, to themselves, their spouses, and their dependents. These benefits range from disability compensation to employment and education assistance, training, healthcare and even life insurance, many managed by the Department of Veteran Affairs and in most cases are free or offered at a very low cost.

Regardless of whether or not a service member had difficulties transitioning, some refrain from talking about their service. In these instances, it is important to not take offense to the situation or the veterans’ refusal to discuss their service experience. Some are unable to discuss their service because of the nature of their job and may be prohibited from talking about specifics, while other veterans may have been affected by a traumatic experience and would rather not relive it. An alternative is that some veterans are just uncomfortable with the labels “hero” or “warrior”. Those who served in support roles or never deployed may feel undeserving of the warrior title, while others believe they were only doing their job and would rather not be singled out as being special. In sum, when veterans are comfortable talking about their service, they will.

I hope you have enjoyed this blog series and gained a little insight about a very small population along the way. If you would like to learn more about veterans and see some of the topics not covered in my three blog series, I recommend you read “100 Questions & Answers about Veterans’, by Michigan State University School of Journalism and is available on Amazon and other online book retailers.

Guina, R. (2010, November 10). Types of military discharges. In The Military Wallet. Retrieved June 3, 2018, from https://themilitarywallet.com/types-of-military-discharges/

Newman, L. (2010, November 10). Types of military discharges. In VA benefit blog. Retrieved May 27, 2018, from https://vabenefitblog.com/types-of-military-discharge/

Morin, R. (2011, December 8). The difficult transition from military to civilian life. Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 17, 2018, from https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2011/12/08/the-difficult-transition-from-military-to-civilian-life

For more information on Moraine Park, visit morainepark.edu.